Astrophotography: searching for nuggets, company always welcomed

You see, for those who have not ventured into trying t0 capture deep sky objects such as nebulas, spiral galaxies and star clusters, you need as dark of an area that you can get. What this translates to, at least in South Florida, is a setting up shop somewhere between an alligator pit and one of the many Everglades restoration cells. I would venture to say that any further out from our beloved "Area 27" or "Area 51", you might run into a location where no one but Hiaassen's Clinton Tyree, a.k.a. "Skink" would feel comfortable at that time of night.

I've describe this activity to people in that it's somewhat like camping...minus the tent, sleeping bag or camp fire...add a temporary table, foldable chair, tons of equipment and the only lights you have with you, other than your computer screen, are the LED's on your equipment, the big red beacon on your forehead (for illumination) and perhaps your cell phone lighting up because it's your wife telling you how late it is.

I think a lot of my friend who see my pictures think that Astrophotography is a limited time event...somewhat like an eclipse. Perhaps it conjures up the idea that as you step into the natural planetarium of dark skies for that short window in time and the heavens are revealed to you. It is in fact, just that, granted you know how to see it or what to expect. And, the time, well, it ain't short unless you compare it to a direct flight from Miami to Sydney, Australia.

One important aspect is that our human eyes, in low light or darkness, does not see color (rods vs. cones) so the spectacular greens, blues and reds for nebulas are just not detectable my the naked eye. You need a good CCD to capture and translate wavelength your eyes are adapted to. I remember in trying to impress my wife when we first dated, I showed her the Orion's Great Nebula through my little C5. Her response was "what am i looking at? Oh, that gray blob? looks like a smudge on your lens!" That too, is why, visual astronomy just doesn't cut it for me. So being out in the dark staring through an eyepiece might not what be what most people expect.

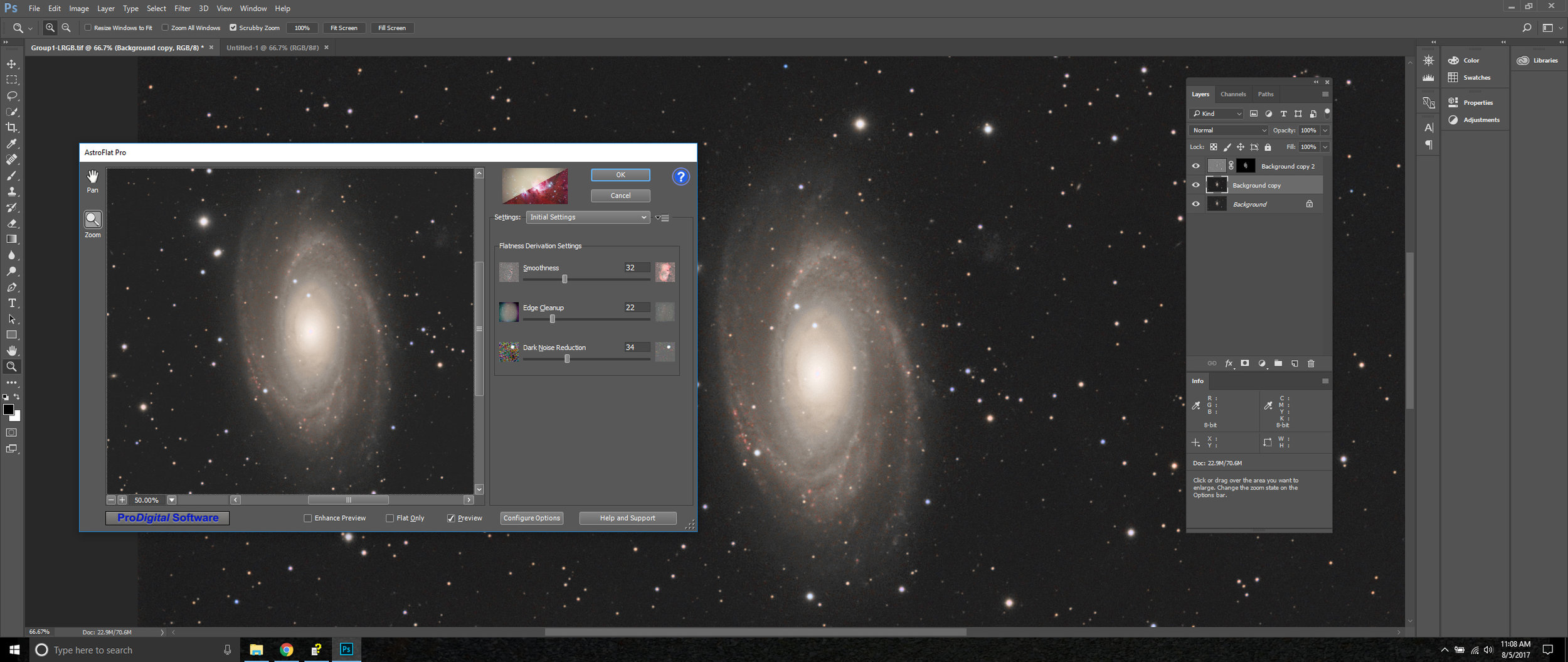

The other thing is the arduous task of capturing these images. My last blog post really paints the picture this hardship but I would like to use another analogy. These photos, as amateur and rough as mine might be, are like diamonds. Most people who see diamonds see it in an air-conditions show room, polished and mounted under perfect lighting. Although in the back of their minds, they know that it takes a lot to there, I'm certain, they have no interest in joining the next dig.

The pictures from myself and fellow astrophotographers are our nuggets as polished and framed as best as our tools and skills can take us. However, what happened to get there is that we load and unload heaps of equipment, climb down the mines with our pick axes (some of us have jack hammers) and chip away night after night, hours on end for that raw nugget. Then sit the next day for hours trying to grind that nugget into shape, color and clarity. Your nugget might not turn out to be of the finest GIA certification grade, but if you have a successful dig the night before, they are still your gems.

Anyways, in actual terms, the whole process is such that if you've made it past the equipment trouble shooting phase, which could be several hours alone, you spend the entire time (4-5 hours) sitting in the dark monitoring your tracking, guiding, data capture stream, cloud/weather patterns and mosquito repellent levels, as some images could take 3 hours of camera time on a target just to get decent data to work with. Oh, did I mention how huge the mosquitos were? On my first outing, I've mistook one for a dragonfly in the dark.

In fact, being in the boonies in the middle of the night was a big factor which kept me from doing it full-bore in the past and an obstacle i had to overcome when deciding to get back into it.

Still, even nursing multiple mosquito bites and having to use a luffa to scrub off the blanket of caked-on sweat upon arriving home, I can not express the amount of reward you feel when you get that successful image. It is truly priceless. Also, the friendships I've made with my fellow astrophotographers are just as priceless.

So, I certainly welcome all my friends who would like to join me/us. We'd love and could use the company, my suggestion if you do join us, it would definitely be more fun for you if you bring your own pick axe.

Charles Lillo

I’ve been a dedicated to Squarespace fan for 20 years. Love the product, people and company.